Open Source Software Licenses: How to choose the right one for your business?

Hi, it's Abel from Red River West, welcome to this second edition of Commit Pulse: our new newsletter about Open Source, and infra software. Today, I'll discuss about Open Source software licenses with the goal to provide a guide to anyone who is interested about building an Open Source business, investing in Commercial Open Source or just using an Open Source project.

When building a Commercial Open Source business, selecting the right license is one of the most crucial decisions you'll make. Your choice of license defines how your software can be used, modified, and shared, impacting everything from community adoption to monetization strategies. One major reason many Open Source companies struggle to monetize (often alienating their community in the process) is their failure to choose an appropriate license from the start. Beyond simply making a choice, it’s equally important to communicate the reasons behind that decision to foster trust within your community. Your license is an important part of the pact you make with this community, and to create trust, you’ll need to explain the rationale behind your choice of license very clearly (especially if you are going for something not that permissive).

More than making a choice, communicating about why you made this choice is also crucial to creating trust within your community. For Open Source companies, trust is everything, and to create this trust, you’ll need to explain your choices.

This guide provides concrete insights to help founders choose the ideal license tailored to their specific goals and business model. Whether you're:

Initiating a new project and unsure which license to choose

Considering switching licenses for an existing project (very complicated)

Simply eager to learn more about Open Source licensing strategies

Note: This article focuses on software licenses. For information about AI models or dataset licenses, subscribe to Open Source Pulse. Our next month's article will cover those topics.

The Basics of Software Licenses

Open Source licenses fall into two main categories: permissive licenses and copyleft licenses. In this article, I will also address Fair code licenses which are not Open Source licenses, but still offer some of the advantages of Open Source:

Permissive Licenses: These licenses are relatively... permissive (yep it's in the name 😅), allowing the software to be used, modified, and distributed with minimal restrictions. Examples include the MIT License, Apache License 2.0, and the BSD License.

Copyleft Licenses: These licenses impose more restrictions to ensure that derivative works are distributed under the same license (if you are building software that is derivative of a project with a copyleft license, it has to be Open Source). This approach aims to keep the software and its derivatives open. The GNU General Public License (GPL) is the best-known copyleft license.

Fair code licenses: Fair code licenses are not Open Source because they impose usage restrictions, typically prohibiting commercial use without permission, which violates the Open Source Definition's requirement for unrestricted use. However, they still offer some advantages that are comparable to Open Source (the code is available for everyone to audit download, host, etc.). Companies typically choose fair-code licenses to:

Ensure the software remains freely available for non-commercial use while requiring commercial users to pay for a license

Prevent cloud providers from repackaging their product and redistributing it for financial benefit

I wouldn’t say that choosing a Fair code license is “bad” in itself, but if you do so, bear in mind that you will not be an Open Source company so don’t communicate as one. Also, I would particularly advise against changing the license of an existing project to Fair code. Indeed, you might end up losing an important part of your community in the process and breaking the trust of your users.

You can also find other types of licenses made for Open Source AI models, but we will talk about them in our next article.

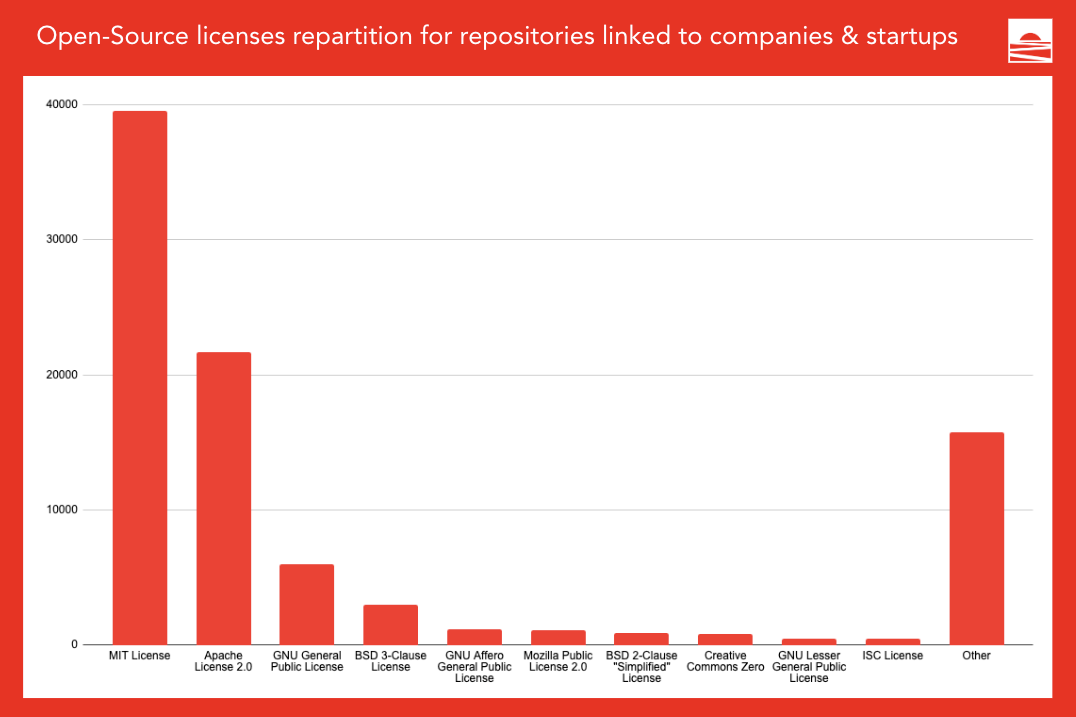

In each of these categories, you can find multiple licenses. The most popular licenses by far are MIT and Apache 2.0 which are both permissive. In the graph below, you can see the repartition of licenses for Github repositories that are linked to companies (using Crunchbase as a company database).

More than 70% of licenses used by Commercial Open Source companies are Permissive and less than 5% of them are Fair-code licenses. However, when you look at the top 10 biggest Open Source companies in terms of valuation, it switches. Only 3 out of them have permissive licenses (mostly Apache 2.0), while 4 have a Copyleft License (GPL, AGPL, and CPAL) and 3 have a Fair-code license (BSL and SSPL). Some of them have switched to less permissive licenses recently creating tension within their community.

Why you should choose wisely your license: a few examples

Open Source licensing issues have impacted several companies over the years, leading to conflicts within the community and challenges to their business models.

Docker for example is one of the most iconic Open Source success stories in terms of adoption but also one of the most famous cases of struggling to monetize. The fact that they used an Apache 2.0 license for its core container runtime and tooling allowed major cloud providers, such as AWS, Google Cloud, and Microsoft Azure, to integrate Docker into their managed container services without compensating the company. As a result, while Docker became synonymous with containers, the company itself faced severe financial difficulties, ultimately needing to restructure and sell its enterprise business to Mirantis in 2019.

In the last years, a couple of big Open Source businesses tried to avoid facing the same issues and changed their licenses from Open Source to Fair code. But in the process, they abandoned their Open Source principles and alienated their community. Here are a few examples:

HashiCorp: In 2023, HashiCorp switched its Terraform product from the Mozilla Public License (MPL) to the Business Source License (BSL), which restricts commercial use. This decision led to significant backlash from the community, who felt betrayed by the sudden shift in licensing terms.

ElasticSearch: ElasticSearch switched from the Apache 2.0 license to the SSPL in 2021 to prevent cloud providers from offering its services without contributing back. This led to a fork of the AWS project into OpenSearch, fracturing the community. However, due to backlash from the community, Elastic ultimately decided to dual-license its software under both the Elastic License 2.0 and the Server Side Public License. Despite the dual licensing strategy, the OpenSearch project continues to thrive as a fully Open Source alternative maintained by AWS and the community, and Elastic lost the trust of an important share of the Open Source community.

Other companies like Confluent and MongoDB also made this change always resulting in strong backlashes within their community. But all of that for what?

Indeed, amongst all of these companies, none of them have known a notable change in their revenue growth rate when changing their licenses, and in terms of company valuation, some of them like HashiCorp or Confluent saw a real negative impact from license change. This article by Rachel Stephens explores the area well.

So why betray your community and bother going through hell? I think that they should have kept their Open Source license. But maybe they could have also made a better choice when choosing their license at first.

Choosing the right license for your Open Source business

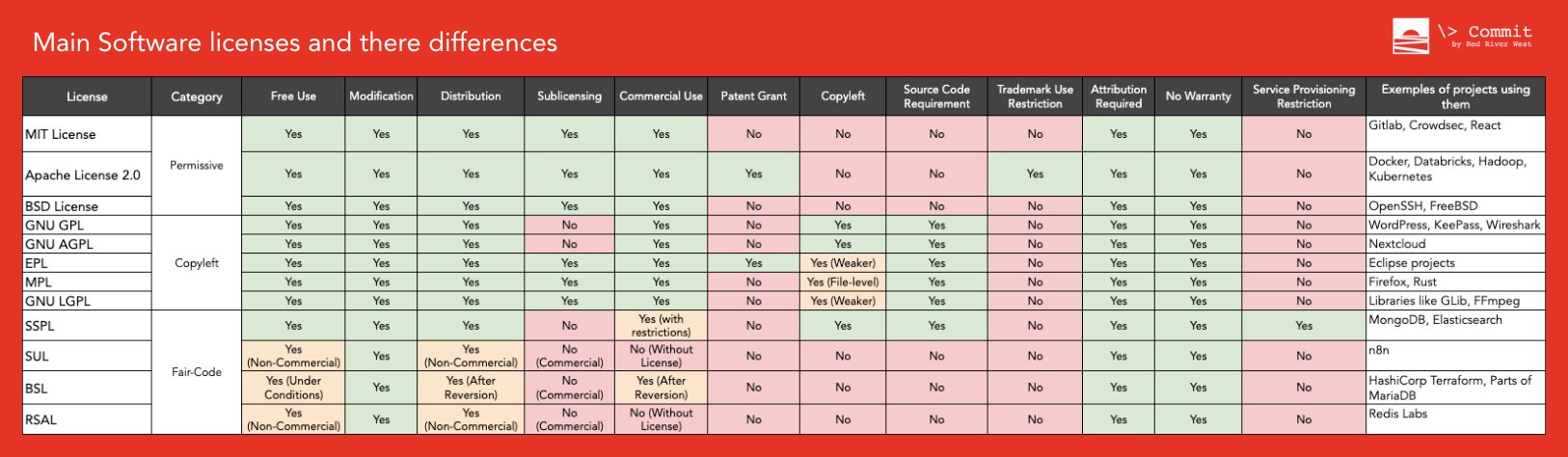

The type of license you choose should align with your business model and strategic objectives. In the table below, you can see the differences between the most well-known licenses and some examples of companies using them.

Like me before, maybe you have seen other tables like this one without having an in-depth understanding of what each column means in "real life". So here are a few explanations:

Free Use: Whether the license allows the software to be used for any purpose.

Modification: Whether the license allows modifications to the software (quite self-explanatory I'll admit 😅).

Distribution: Distribution refers to the act of sharing or providing copies of the software to others, whether the software is in its original form or modified. This can include distributing the software as part of a product, posting it online, or sharing it via other means.

Sublicensing: Whether the license grants anyone the right to license the software to third parties. When you sublicense software, you are effectively allowing someone else (e.g. a Cloud provider) to distribute or license the software under specific terms that you dictate.

Commercial Use: Whether the license allows the software to be used for commercial purposes. Not allowing that at all is a very important restriction and in my opinion kinds of defeats most of the interests of Open Source (i.e. it makes you more "Freemium" than Open Source).

Patent Grant: Whether the license includes a patent grant, protecting users from patent infringement claims by contributors. If you have patents on certain techniques or algorithms used in your project can choose to put a patent grant (with Apache 2.0 for example) and thus allow people to use these techniques freely. The other solution would be to choose a license without a patent grant which will allow you to sue people using your patented algorithms if you want or need to (but as it is a risk for them, it might prevent people from using your product).

Copyleft: Copyleft is called "copyleft" as a playful twist on "copyright," emphasizing that rights are left to users rather than being restricted. Whether the license requires derivative works to be licensed under the same license, ensuring they remain Open Source. Concretely, if you have a Copyleft license, any company (including you) that will build upon your project will need to Open Source what they are building.

Source Code Requirement: This refers to whether it is required to provide the original source code when distributing compiled versions of the software, like an executable file. This ensures that recipients have access to the code used to create the software, allowing them to modify, study, or redistribute it. It's a key feature of licenses like the GNU GPL, which aims to maintain transparency and openness in software development.

Trademark Use Restriction: This refers to whether the license limits how you can use the names, logos, or other trademarks associated with the software. For example, you might be able to use and modify the software freely, but you can’t call your modified version "Firefox" because "Firefox" is a trademark of Mozilla.

Attribution Required: Whether the license requires that credit be given to the original authors.

No Warranty: This means the license disclaims any guarantees about the software, indicating it is provided "as is" without any promises of performance, reliability, or suitability for any purpose. Users accept the software at their own risk, and the authors are not liable for any issues that arise from using it.

Service Provisioning Restriction: It defines the limitations a license places on offering the software as a hosted service (SaaS). For instance, the SSPL mandates that companies offering the project with a SaaS model must either Open Source their entire service infrastructure or acquire a commercial license. This requirement prevents cloud providers from making money of the software without giving back to the community or the original developers.

Ok, so now you know the specificities of each license. But which one should you choose?

🔓 Permissive licenses

Who Should Use Them:

Companies seeking broad adoption: These licenses maximize the distribution and use of your software, encouraging adoption even in proprietary projects. This helps build a user base and ecosystem quickly. Projects with permissive licenses often gain more developer support and easier implementation in large companies.

Companies with clear monetization strategies: If you don't primarily plan to rely on hosting/SaaS and have established monetization methods that won't be “too much” undermined by others forking or reselling your project, permissive licenses can boost adoption. However, if you later need to monetize through hosting, this becomes challenging.

Viable Business Models with Permissive Licenses:

Open-Core: You can Open Source the core of your product using a permissive license and sell paid features needed by enterprises and other types of users on top. However, proceed with caution: many open-core businesses struggle because the monetized features are either too easy to replicate or provide minimal additional value beyond an Open Source product that already meets the needs of most enterprises. Striking the right balance is essential but can be challenging to accomplish.

Open Peripheral: When your main product is closed-source but you want to distribute some tools on top of it as Open Source to build community engagement, you can use permissive licenses for these products.

Consulting/Services: When your monetization strategy involves offering support for an Open Source project, permissive licenses help build a large potential customer base.

When to Avoid Permissive Licenses:

If you want to ensure that modifications and improvements to your software are shared back with the community, permissive licenses may not be the best choice. With these licenses, companies can build upon your project without giving back, which may undermine your goal of fostering a collaborative, open ecosystem.

If you lack a significant competitive advantage from your community, closed-source features, or team expertise (as competitors could easily build competing versions)

Choosing the Right Permissive License:

MIT License: Best for simplicity and broad compatibility. The most permissive option, requiring only inclusion of the original license and copyright notice.

Apache License 2.0: Ideal when patent protection matters. Includes patent grants protecting you and users from lawsuits, plus provisions for trademarks, contributions, and sublicensing. More complex than MIT (requires NOTICE file).

BSD License: Similar to MIT but provides control over how your product's name and contributors' names are used for promotion or endorsements.

🔏 Copyleft Licenses

Who should use them:

Companies wanting to ensure that any modification to their software will remain Open Source: If your goal is to ensure that any modifications or derivatives of your software remain Open Source, copyleft licenses are ideal. They enforce that all derivative works are also Open Source.

Companies preventing proprietary forking: Licenses like GPL (used by WordPress) prevent companies from taking Open Source code, modifying it, and releasing a proprietary version.

When should you avoid it?

If you want your software used in proprietary environments, especially commercial products needing to remain closed-source. E.g. Google avoids using the Copyleft code because it requires any modified or derivative work to be Open Sourced, which could force them to disclose proprietary technology and compromise their competitive advantage.

If your business model involves dual licensing (offering the software under a copyleft license for Open Source use and a proprietary license for commercial use), you might still prefer a permissive license if you want to avoid the complexity of managing the obligations that come with copyleft. In some cases, offering a purely permissive license and monetizing through other means could be simpler and more effective.

If you want to avoid legal complexity, copyleft is not the best fit for you. You will need the legal resources to enforce your copyleft requirements if they are important for your business.

If a significant portion of your revenue depends on hosting/SaaS or certain Open-Core models, particularly with AGPL, which could force you to Open Source components you prefer to keep proprietary

Choosing the Right Copyleft License:

GNU GPL: For strong copyleft enforcement, ensuring all derivative works remain Open Source under the same license

GNU AGPL: For software used in networked environments, requiring source code availability to users interacting with the software over networks

LGPL: For libraries that might be linked with proprietary software without requiring the proprietary code to be Open Source

MPL or EPL: For file-level or weaker copyleft requirements. These allow use in closed-source works but require improvements to the work itself to remain copyleft. Best option for infrastructure/developer tools targeting B2B with broad adoption goals.

RPL: Unlike other copyleft licenses that primarily enforce openness for derivative works (like the GPL) or networked use cases (like the AGPL), the RPL goes a step further by requiring that any software incorporating or linking to RPL-licensed code also be open-sourced. This makes it significantly stricter in terms of preventing proprietary adoption while fostering a fully open ecosystem. Ideal for projects where ensuring community-driven innovation and preventing proprietary use is a priority.

🔐 Fair-Code Licenses

Who should use them:

Companies that derive the majority of their revenue from offering hosted versions of their products: SSPL effectively protects against cloud provider exploitation by requiring companies providing your product to either Open Source their entire service stack or purchase a commercial license.

Companies with uncertain monetization strategies: If you want Open Source benefits (accessible code, community support, self-hostable products) without needing extensive contributors, and have no clear monetization plan, Fair-code may be appropriate. Starting with Fair-code and moving to permissive is better than the reverse.

Companies wanting time-limited commercial protection: Business Source License (BSL) protects initial development while automatically transitioning to a more permissive license after a predetermined period.

When should you avoid it?

If widespread adoption is your priority, especially among businesses incorporating your software into proprietary products

If you aim to form partnerships or integrate with commercial platforms

If you need substantial community contributions (many Open Source contributors avoid Fair-Code projects)

⚠️ If you want to call your product Open Source. No Fair-code is not Open Source, so you can’t say that you are the “Open Source alternative to” or use that as a marketing means because it would be false and developers won’t let that pass.

Choosing the Right Fair-Code License:

SSPL: When preventing cloud providers from offering hosted versions without contribution is your primary concern

SUL or RSAL: When you want to restrict commercial use and require businesses to pay while allowing free non-commercial use and contributions

BSL: When you need a commercial protection period before fully open-sourcing, ideal for initial revenue generation

⭐️ Dual Licensing

If you want the best of both worlds, you can also release a part of your software under an Open Source license and a part of it under a commercial license. You can even choose to use a permissive license for a part of it and a fair-code license for another one. It's particularly useful for Open-Core businesses. If you choose this solution and it's possible, I’d advise you to try to use a permissive license and not a copyleft license for the part that you want to "Open Source". It will foster your community and prevent legal nightmares.

Who Should Use Them:

Projects requiring both Open Source engagement and commercial flexibility: Dual licensing is particularly useful when you want to build a strong Open Source community but still want to monetize from closed-source features or products. I would advise most Open-Core businesses to choose this approach.

Projects that want to make sure enterprise companies using their code are contributing financially, but still want to have a real Open Source version of their product (which is not really the case with Fair-Code).

Drawbacks of dual licensing

Increased complexity in managing different licensing agreements, requiring significant legal and administrative resources. Making an error could result in other persons building a competing version of your software. E.g. when Semgrep removed critical features of its engine behind a commercial license, a consortium of organizations decided to build a competitor based on their Open Source version: Opengrep.

Potential avoidance by companies concerned about legal and compliance risks

It may be perceived as restrictive, deterring some developers. Clear communication about what remains free versus paid is essential.

🌍 License enforcement and differences across international borders

When selecting a license, consider that copyright laws and enforcement mechanisms vary internationally. What works in one jurisdiction may have different implications in another

In the United States, Open Source licenses have strong legal backing through copyright law. Courts have generally upheld these licenses as valid legal agreements, giving developers reasonable protection against misuse of their code.

The European Union provides similar protections, though with regional variations. Germany stands out as particularly favorable for license enforcement, with several successful GPL compliance cases establishing strong precedents. France and the Netherlands also provide relatively robust frameworks for enforcing Open Source terms. In France for example, the CeCILL license (created by CEA, CNRS, and INRIA) serves as an adaptation of international Open Source licenses (like the GPL) to comply with French law, offering a legally robust framework while preserving the principles of copyleft and Open Source distribution.

The situation becomes more challenging in regions like parts of Asia, Eastern Europe, and South America. In China, for example, copyright enforcement for software in general remains inconsistent, making Open Source license enforcement particularly difficult. Similar challenges exist in Russia, where legal recourse for foreign copyright holders can be limited.

Most successful enforcement doesn't involve courtrooms at all. Organizations like the Software Freedom Conservancy typically start with educational outreach and compliance assistance. Only when these efforts fail do they consider legal action, and even then, most cases settle quietly through negotiation rather than litigation.

When planning your licensing strategy, consider not just the theoretical protections a license offers, but how practically enforceable it will be in your target markets. A strong copyleft license might seem protective on paper, but if you lack the resources to enforce it globally, you might be better served by a simpler permissive license with clear boundaries.

Conclusion

Selecting the right Open Source license is a critical decision that will influence the trajectory of any Open Source business. As you saw in this article there is no one-size-fits-all answer, but you have to choose the right license depending on your business model, your needs, your threats, etc. Making the right choice from the start and communicating about it is very important, so if you consider building an Open Source business think about it thoroughly. If you want to contact me to discuss it, feel free to do it at abel@redriverwest.com.